Revisited: House & Garden

Specialist Profile

From House & Garden 2014

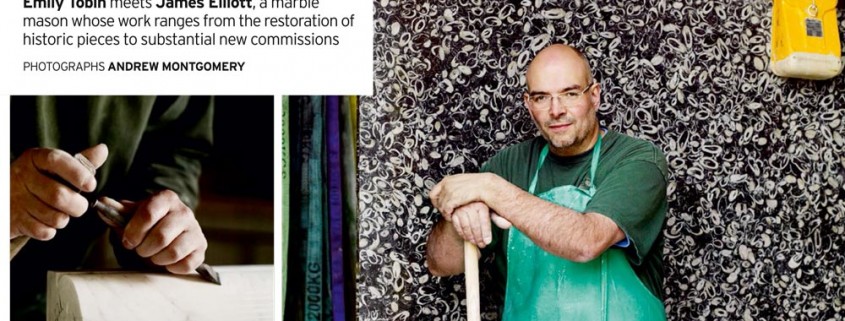

Emily Tobin meets James Elliott, a marble mason whose work ranges from the restoration of historic pieces to substantial new commissions.

Surrounded by endless green fields and little else, James Elliott’s workshop is in the middle of nowhere. And that’s just what he wants. Here, he is at liberty to make as much noise as he likes, and when you are working with marble and heavyweight machinery, it is possible to create quite a clamour.

The building shrieks and roars as solid blocks of Purbeck, Petworth and Ashford black marble are carved and cut with extraordinary precision by a fleet of impressive-looking contraptions.

James specialises in architectural masonry, repair and historical restoration. His work is always very diverse – ranging from Soane-style chimneypieces to Pietra Dura inlay and ecclesiastical marbles. He has even made a complete set of hot and cold tap tops for Chatsworth House in Duke’s Red and Derbyshire Blue John. ‘You never know what will come in the door,’ he says. With every new commission comes a set of new challenges: ‘We specialise in fiendishly complicated.’

![specialist-prof-april-2014[2]-1](https://jameselliott.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/specialist-prof-april-20142-1-213x300.jpg) The son of a vicar, James set out to be a cabinetmaker, but, having completed his training, he took a job at the marble yard opposite his father’s church in Elstree. Dissatisfied with the way the owners treated their product, he realised that ‘it wasn’t simply a matter of cutting the stone into a square and sending it out the door’, but rather that marble needed to be sensitively handled. And so, he set up on his own.

The son of a vicar, James set out to be a cabinetmaker, but, having completed his training, he took a job at the marble yard opposite his father’s church in Elstree. Dissatisfied with the way the owners treated their product, he realised that ‘it wasn’t simply a matter of cutting the stone into a square and sending it out the door’, but rather that marble needed to be sensitively handled. And so, he set up on his own.

Three decades and two workshops later, James has established an international reputation and a loyal client base. He is insistent that all technical demands of a project are fully resolved before work commences, rendered in 3-D. James points out one particularly complicated sketch that indicates how the 59 separate pieces of a bath will slot together to form a sleek, curved tub.

The colossal machines that populate the workshop floor are used to edge, split, polish and profile the marble. When I visit, a table base fixed in the lathe is cut and turned from Kilkenny black marble with rigorous exactness. But most of the final touches are done by hand – using a hammer and chisel.

Recent innovations in 3D printing have been instrumental to the way James works, although in exactly what way, he is reluctant to say: ‘If I told you, I’d have to shoot you,’ he deadpans. He has developed certain methods that he does not think anybody else uses, which explain his reticence.

Attention to detail is paramount. James shows me how veined marble is book-matched: the stone is split, rather like slicing a loaf of bread; then the slabs are polished on alternate sides so that, when they are side-by-side, the veining forms an unbroken pattern.

![specialist-prof-april-2014[2]-2](https://jameselliott.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/specialist-prof-april-20142-2-e1427013984918.jpg) Six years ago, James was charged with the seemingly impossible task of reconstructing a bathroom that had been smashed to pieces; the remains had been gathered together in 42 bags of rubble. ‘It was like an archaeological dig,’ he says. Yet miraculously, he managed it, and today he is able to show me photographs of the room, which is made from Rosso Antico marble and functions fully with no evidence of its fractured past.

Six years ago, James was charged with the seemingly impossible task of reconstructing a bathroom that had been smashed to pieces; the remains had been gathered together in 42 bags of rubble. ‘It was like an archaeological dig,’ he says. Yet miraculously, he managed it, and today he is able to show me photographs of the room, which is made from Rosso Antico marble and functions fully with no evidence of its fractured past.

In another recent coup, James was granted access to 33 Swedish quarries filled with a wonderful, sludgy green marble that has not been used since the Seventies. In the yard outside his Rutland workshop, he points to what at first glance seems to be an unremarkable block of the stuff, rough around the edges and greyish in colour. When it is cut, the smooth marble interior is revealed. ‘It is a bit of a funny colour, but it’s an amazing material,’ says James. This chunk of stone will soon be transformed into the aforementioned decadent bath for a London house.

With his extensive geological knowledge, uncompromising approach – he is not afraid to tell someone how to better their design – and mastery of the craft, it is no surprise that James has such a committed client base. But this too, rather like his methodology, is a closely guarded secret. He does admit to usually having ‘one or two country houses on the go,’ and if you keep your eyes peeled as you stroll past the shop fronts in the Pimlico Road, you may just chance upon one of his creations.

From: April 2014 House & Garden

Photographs: Andrew Montgomery